Sẹo quá mức hình thành do hậu quả bất thường của việc lành vết thương sinh lý và có thể phát sinh sau bất kỳ tổn thương nào đến lớp hạ bì sâu. Bằng cách gây đau, ngứa và co rút, sẹo quá mức ảnh hưởng đáng kể đến chất lượng cuộc sống của bệnh nhân, cả về thể chất và tâm lý. Nhiều nghiên cứu về sẹo phì đại và hình thành sẹo lồi đã được tiến hành trong nhiều thập kỷ qua và đã dẫn đến hàng loạt các chiến lược điều trị để ngăn ngừa cũng như làm giảm sự hình thành sẹo quá mức. Tuy nhiên, hầu hết các phương pháp điều trị vẫn chưa đạt yêu cầu về mặt lâm sàng, mà có thể do còn chưa hiểu biết rõ về các cơ chế phức tạp làm cơ sở cho quá trình sẹo và co rút vết thương. Trong bài tổng quan này, chúng tôi tóm tắt những hiểu biết hiện tại về sinh lý bệnh cơ bản hình thành sẹo lồi và sẹo phì đại và thảo luận về các phương pháp điều trị đã được áp dụng cũng như các chiến lược điều trị mới.

Chỉ riêng ở các nước phát triển mỗi năm Tổng cộng có 100 triệu bệnh nhân phát bị sẹo do sau 55 triệu ca phẫu thuật tự chọn và 25 triệu ca phẫu thuật sau chấn thương (1). Sẹo quá mức hình thành do hậu quả bất thường của việc lành vết thương sinh lý và có thể phát sinh sau bất kỳ tổn thương nào đến lớp hạ bì sâu, bao gồm tổn thương bỏng, vết rách, trầy xước, phẫu thuật, xỏ khuyên và tiêm chủng. Bằng cách gây ngứa, đau và co rút, sẹo quá mức có thể ảnh hưởng đáng kể đến chất lượng cuộc sống của bệnh nhân, cả về thể chất và tâm lý.

Sẹo phát triển quá mức được mô tả lần đầu tiên trong văn bản giấy cói Smith khoảng 1700 trước Công nguyên (2). Nhiều năm sau Mancini (năm 1962) và Peacock (năm 1970) đã phân biệt sẹo quá mức thành hình thành sẹo lồi và sẹo lồi. Theo định nghĩa của họ, cả hai loại sẹo đều tăng trên mức độ da, nhưng trong khi sẹo phì đại không vượt quá vị trí tổn thương ban đầu, sẹo lồi thường dự đoán vượt ra ngoài lề vết thương ban đầu (3,4). Tuy nhiên, sự khác biệt lâm sàng giữa sẹo phì đại và sẹo lồi có thể là vấn đề. Việc xác định không đúng loại sẹo có thể dẫn đến việc quản lý sự hình thành sẹo bệnh lý không phù hợp và đôi khi góp phần vào việc đưa ra quyết định không phù hợp liên quan đến phẫu thuật tự chọn hoặc thẩm mỹ (5).

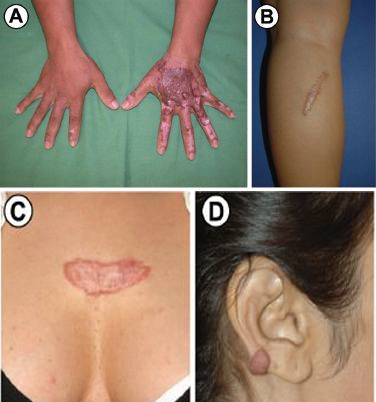

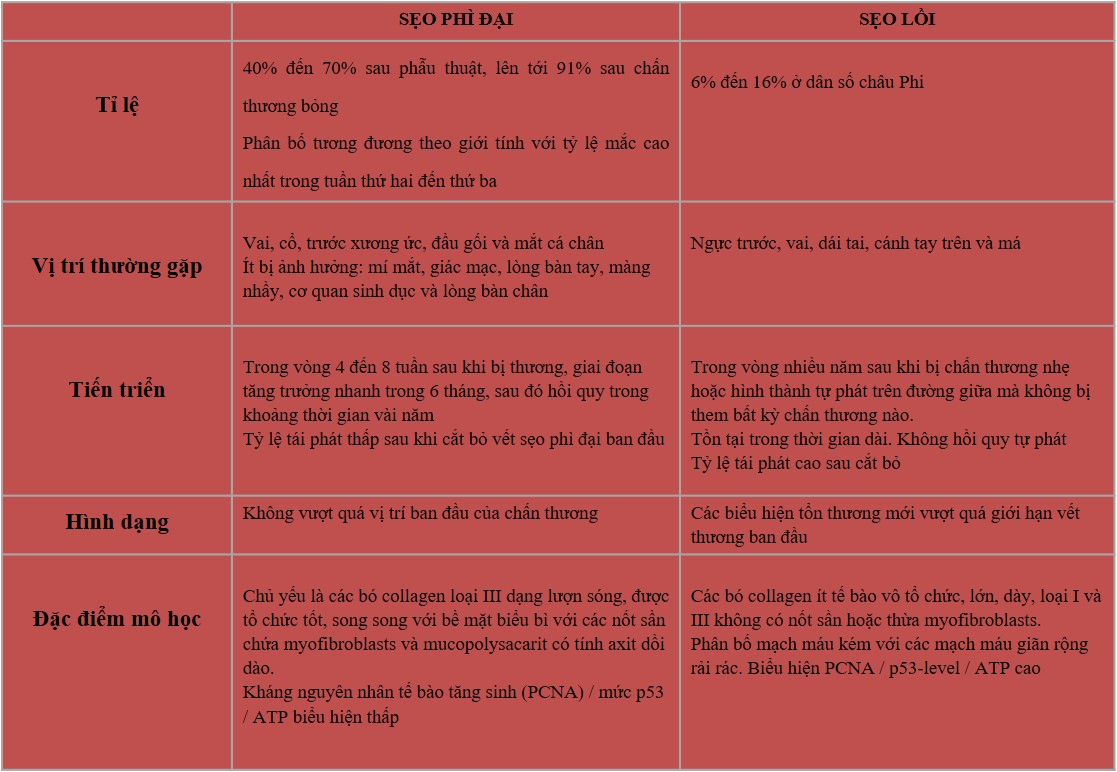

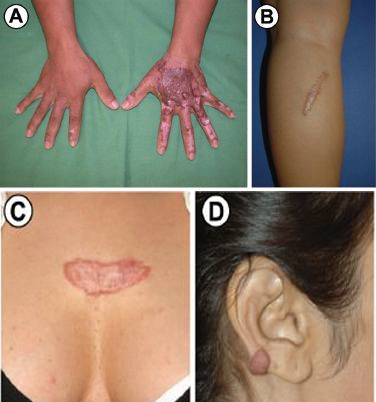

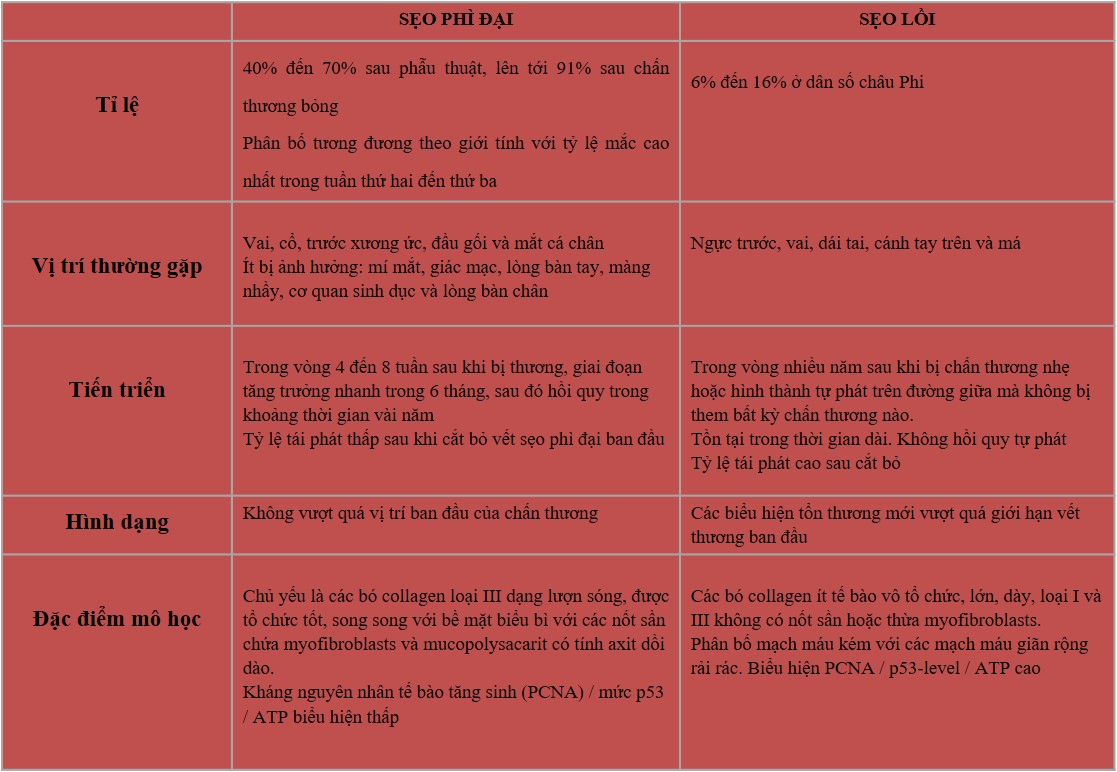

Mặc dù có những điểm tương đồng lâm sàng giữa sẹo phì đại và sẹo lồi, nhưng những khác biệt về lâm sàng, mô học và dịch tễ học (Bảng 1 và Hình 1) chỉ ra rằng có thể khác biệt với nhau ở từng cá thể (5,6).

Hình 1

Biểu hiện lâm sàng của sẹo phì đại và sẹo lồi.

Sự phát triển của các vết sẹo phì đại sau khi bị bỏng nước sôi (A); sẹo phì đại ở chân dưới 4 tháng sau phẫu thuật (B);

sẹo lồi trên ngực sau hai ca phẫu thuật nhỏ (C); sẹo lồi trên tai phải, không có tiền sử chấn thương (D).

Bảng 1

Đặc điểm lâm sàng

Sẹo phì đại thường xảy ra trong vòng 4 đến 8 tuần sau khi vết thương bị nhiễm trùng, đóng vết thương với lực căng quá mức hoặc chấn thương da khác (7), có giai đoạn tăng trưởng nhanh chóng trong 6 tháng, và sau đó thoái triển dần trong khoảng thời gian vài năm, cuối cùng dẫn đến sẹo phẳng không có triệu chứng gì thêm (8,9). Ngược lại, sẹo lồi có thể phát triển đến vài năm sau khi bị thương nhẹ và thậm chí có thể hình thành một cách tự nhiên trên đường giữa trong trường hợp không có bất kỳ thương tích nào được biết đến. Sẹo lồi cũng tồn tại, thường trong thời gian dài và không thoái triển tự phát (10). Sẹo lồi xuất hiện dưới dạng khối u săn chắc, nhẹ, mềm, có bề mặt sáng bóng và đôi khi là giãn mạch. Biểu mô bị mỏng dần và có thể có các khu vực loét khu trú. Màu từ hồng đến tím và có thể đi kèm với tăng sắc tố (11). Bờ của khối sẹo được phân chia rõ ràng nhưng không đều đặn. Sẹo phì đại có bề ngoài tương tự, nhưng thường là tuyến tính, nếu do phẫu thuật, hoặc sẩn hoặc nốt, nếu do các tổn thương viêm và loét (12). Cả hai tổn thương thường là ngứa, nhưng sẹo lồi thậm chí có thể là nguồn gốc của đau đớn và tăng sản đáng kể (7,9).

Trong phần lớn các trường hợp,

- Sẹo phì đại phát triển ở các vết thương tại các vị trí giải phẫu với độ căng cao, chẳng hạn như vai, cổ, trước xương ức, đầu gối và mắt cá chân (9,12,13),

- Trong khi ngực trước, vai, dái tai, cánh tay trên và má thường thích hợp hơn cho sự hình thành sẹo lồi. Mí mắt, giác mạc, lòng bàn tay, màng nhầy, cơ quan sinh dục và lòng bàn chân thường ít bị ảnh hưởng (14).

- Sau khi cắt bỏ : Sẹo lồi có xu hướng tái phát, sẹo phì đại mới là hiếm (13,15).

Mô học

Về mặt mô học, cả sẹo phì đại và sẹo lồi đều chứa quá nhiều collagen của da. Sẹo phì đại chứa chủ yếu collagen loại III định hướng song song với bề mặt biểu bì với các nốt sần chứa những nguyên bào sợi, sợi collagen ngoại bào lớn và mucopolysacarit có tính axit dồi dào (6). Ngược lại, mô sẹo lồi có thành phần chủ yếu là collagen loại I và III vô tổ chức, chứa các bó collagen nghèo tế bào bóng nhạt không có nốt sần hoặc thừa nguyên bào sợi (Bảng 1) (6,16). Cả hai loại sẹo đều thể hiện sự sản xuất quá mức của nhiều protein nguyên bào sợi, bao gồm cả chất xơ, cho thấy sự tồn tại bệnh lý của các tín hiệu chữa lành vết thương hoặc sự thất bại của quá trình điều hòa thích hợp của các tế bào chữa lành vết thương (16).

Dịch tể học

Sự xuất hiện của sẹo lồi và sẹo phì đại có sự phân bố giới tính bằng nhau và tỷ lệ mắc cao nhất trong tuần thứ hai đến thứ ba (17,18). Tỷ lệ mắc sẹo phì đại thay đổi từ 40% đến 70% sau phẫu thuật đến 91% sau chấn thương bỏng, tùy thuộc vào độ sâu của vết thương (19,20). Sự hình thành sẹo lồi được nhìn thấy ở các cá thể thuộc mọi chủng tộc, ngoại trừ bạch tạng, nhưng những người da sẫm màu đã được phát hiện là dễ bị hình thành sẹo lồi hơn, với tỷ lệ mắc từ 6% đến 16% ở dân số châu Phi (14,21). Khái niệm về khuynh hướng di truyền đối với sẹo lồi từ lâu đã được đề xuất, bởi vì bệnh nhân bị sẹo lồi thường có tiền sử gia đình bị sẹo lồi, không giống như bệnh nhân bị sẹo phì đại. Bayat và các đồng nghiệp (22) đã so sánh hồ sơ của các bệnh nhân gốc Afro-Caribbean bị sẹo lồi ở một vị trí so với nhiều vị trí giải phẫu và thấy bệnh này phổ biến hơn ở các nhóm tuổi trẻ và ở phụ nữ. Một phát hiện quan trọng là hơn 50% bệnh nhân sẹo lồi có tiền sử gia đình sẹo lồi dương tính và tiền sử gia đình có liên quan chặt chẽ với sự hình thành sẹo lồi ở nhiều vị trí trái ngược với một vị trí giải phẫu. Marneros và cộng sự (23) đã nghiên cứu tách biệt hai gia đình có kiểu di truyền sẹo lồi tự phát và xác định mối liên kết với nhiễm sắc thể 7p11 và nhiễm sắc thể 2q23 ở gia đình châu Phi và Nhật Bản. Brown và các đồng nghiệp (24) đã tìm thấy mối liên quan di truyền giữa tình trạng HLA-DRB1 * 15 và nguy cơ phát triển sẹo lồi ở những người da trắng. Ngoài ra, những người mang HLA-DQA1 * 0104, DQB1 * 0501 và DQB1 * 0503 đã được báo cáo là có nguy cơ phát triển sẹo lồi (24). Sự tăng trưởng của sẹo lồi cũng có thể được kích thích bởi các hormon khác nhau, như được chỉ ra bởi một số nghiên cứu trong đó kết quả cho thấy tỷ lệ hình thành sẹo lồi cao hơn ở tuổi dậy thì và mang thai, với sự giảm kích thước sau mãn kinh (18,25,26). Ngoài ra, các hiệp hội miễn dịch của sẹo lồi đã được đề xuất. Một nghiên cứu của Placik và Lewis (27) đã tiết lộ mối tương quan trực tiếp giữa tỷ lệ hình thành sẹo lồi và nồng độ IgE huyết thanh, Smith và cộng sự (28) tìm thấy tỷ lệ mắc các triệu chứng dị ứng cao hơn ở những bệnh nhân bị sẹo lồi so với những người có sẹo phì đại, cho thấy vai trò có thể của các mastocyte trong sinh lý bệnh của sự hình thành sẹo lồi. Các nhà nghiên cứu khác đã báo cáo về mối liên quan giữa sự hình thành sẹo lồi và nhóm máu A (14,29).

.....

còn tiếp

...

References

- Sund B. (2000) New Developments in Wound Care. PJB Publications, London, pp. 1–255.Google Scholar

- Berman B, Bieley HC. (1995) Keloids. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 33:117–23.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Peacock EE Jr, Madden JW, Trier WC. (1970) Biologic basis for the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars. South. Med. J. 63:755–60.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mancini RE, Quaife JV. (1962) Histogenesis of experimentally produced keloids. J. Invest. Dermatol. 38:143–81.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Atiyeh BS. (2007) Nonsurgical management of hypertrophic scars: evidence-based therapies, standard practices, and emerging methods. Aesthetic. Plast. Surg. 31:468–94.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Slemp AE, Kirschner RE. (2006) Keloids and scars: a review of keloids and scars, their pathogenesis, risk factors, and management. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 18:396–402.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wheeland RG. (1996) Keloids and hypertrphic scars. In: Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. Arndt KA, Robinson JK, Leboit PE, Wintroub BU (eds.). Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp. 900–5.Google Scholar

- Alster TS, West TB. (1997) Treatment of scars: a review. Ann. Plast. Surg.39:418–32.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hawkins HK. (2007) Pathophysiology of the burn scar. In: Total Burn Care. Herndon DN (ed.) Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp. 608–19.View ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Murray JC. (1994) Keloids and hypertrophic scars. Clin. Dermatol. 12:27–37.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Al-Attar A, et al. (2006) Keloid pathogenesis and treatment. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 117:286–300.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- From L, Assad D. (1993) Neoplasms, pseudoneoplasms, and hyperplasia of supporting tissue origin. In: Dermatology in General Medicine. Jeffers JD, Englis MR (eds.). McGraw-Hill, New York, pp. 1198–99.Google Scholar

- Muir IF. (1990) On the nature of keloid and hypertrophic scars. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 43:61–9.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Niessen FB, Spauwen PH, Schalkwijk J, Kon M. (1999) On the nature of hypertrophic scars and keloids: a review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 104:1435–58.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Leventhal D, Furr M, Reiter D. (2006) Treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. Arch. Facial. Plast. Surg. 8:362–8.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sephel GC, Woodward SC. (2001) Repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. In: Rubin’s Pathology. Rubin E (ed.). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, pp. 84–117.Google Scholar

- Oluwasanmi JO. (1974) Keloids in the African. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1:179–95.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Moustafa MF, Abdel-Fattah MA, Abdel-Fattah DC. (1975) Presumptive evidence of the effect of pregnancy estrogens on keloid growth: case report. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 56:450–3.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Deitch EA, et al. (1983) Hypertrophic burn scars: analysis of variables. J. Trauma. 23:895–8.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lewis WH, Sun KK. (1990) Hypertrophic scar: a genetic hypothesis. Burns. 16:176–8.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Murray CJ, Pinnel SR. (1992) Keloids and excessive dermal scarring. In: Woundhealing, Biochemical and Clinical Aspects. Cohen IK, Diegelmann RF, Lindblad WJ (eds.). Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp. 500–9.Google Scholar

- Bayat A, et al. (2005) Keloid disease: clinical relevance of single versus multiple site scars. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 58:28–37.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Marneros AG, et al. (2004) Genome scans provide evidence for keloid susceptibility loci on chromosomes 2q23 and 7p11. J. Invest. Dermatol.122:1126–32.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Brown JJ, Ollier WE, Thomson W, Bayat A. (2008) Positive association of HLA-DRB1*15 with keloid disease in Caucasians. Int. J. Immunogenet.35:303–7.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ford LC, King DF, Lagasse LD, Newcomer V. (1983) Increased androgen binding in keloids: a preliminary communication. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 9:545–7.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Schierle HP, Scholz D, Lemperle G. (1997) Elevated levels of testosterone receptors in keloid tissue: an experimental investigation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 100:390–6.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Placik OJ, Lewis VL Jr. (1992) Immunologic associations of keloids. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 175:185–93.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Smith CJ, Smith JC, Finn MC. (1987) The possible role of mast cells (allergy) in the production of keloid and hypertrophic scarring. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 8:126–31.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ramakrishnan KM, Thomas KP, Sundararajan CR. (1974) Study of 1,000 patients with keloids in South India. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 53:276–80.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tredget EE, Nedelec B, Scott PG, Ghahary A. (1997) Hypertrophic scars, keloids, and contractures: the cellular and molecular basis for therapy. Surg. Clin. North Am. 77:701–30.PubMedView ArticlePubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Brown JJ, Bayat A. (2009) Genetic susceptibility to raised dermal scarring. Br. J. Dermatol. 161:8–18.PubMedView ArticlePubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Armour A, Scott PG, Tredget EE. (2007) Cellular and molecular pathology of HTS: basis for treatment. Wound Repair Regen. 15 Suppl 1:S6–17.PubMedView ArticlePubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Wynn TA. (2004) Fibrotic disease and the T(H)1/T(H)2 paradigm. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:583–94.PubMedPubMed CentralView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Doucet C, et al. (1998) Interleukin (IL) 4 and IL-13 act on human lung fibroblasts. Implication in asthma. J. Clin. Invest. 101:2129–39.PubMedPubMed CentralView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kamp DW. (2003) Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the inflammation hypothesis revisited. Chest. 124:1187–90.PubMedView ArticlePubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Ladak A, Tredget EE. (2009) Pathophysiology and management of the burn scar. Clin. Plast. Surg. 36:661–74.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Butler PD, Longaker MT, Yang GP. (2008) Current progress in keloid research and treatment. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 206:731–41.PubMedView ArticlePubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Ishihara H, et al. (2000) Keloid fibroblasts resist ceramide-induced apoptosis by overexpression of insulin-like growth factor I receptor. J. Invest. Dermatol. 115:1065–71.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tuan TL, Nichter LS. (1998) The molecular basis of keloid and hypertrophic scar formation. Mol. Med. Today. 4:19–24.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Smith JC, et al. (2008) Gene profiling of keloid fibroblasts shows altered expression in multiple fibrosis-associated pathways. J. Invest. Dermatol.128:1298–310.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bullard KM, Longaker MT, Lorenz HP. (2003) Fetal wound healing: current biology. World J. Surg. 27:54–61.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Szulgit G, et al. (2002) Alterations in fibroblast alpha1beta1 integrin collagen receptor expression in keloids and hypertrophic scars. J. Invest. Dermatol. 118:409–15.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kose O, Waseem A. (2008) Keloids and hypertrophic scars: are they two different sides of the same coin? Dermatol. Surg. 34:336–46.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bock O, et al. (2005) Studies of transforming growth factors beta 1–3 and their receptors I and II in fibroblast of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Acta. Derm. Venereol. 85:216–20.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Schmid P, et al. (1998) Enhanced expression of transforming growth factor-beta type I and type II receptors in wound granulation tissue and hypertrophic scar. Am. J. Pathol. 152:485–93.PubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Lee TY, et al. (1999) Expression of transforming growth factor beta 1, 2, and 3 proteins in keloids. Ann. Plast. Surg. 43:179–84.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Xia W, et al. (2004) Complex epithelial-mesenchymal interactions modulate transforming growth factor-beta expression in keloid-derived cells. Wound Repair Regen. 12:546–56.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lu L, et al. (2005) The temporal effects of anti-TGF-beta1, 2, and 3 monoclonal antibody on wound healing and hypertrophic scar formation. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 201:391–7.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cordeiro MF, et al. (2003) Novel antisense oligonucleotides targeting TGF-beta inhibit in vivo scarring and improve surgical outcome. Gene Ther.10:59–71.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Shah M, Foreman DM, Ferguson MW. (1992) Control of scarring in adult wounds by neutralising antibody to transforming growth factor beta. Lancet. 339:213–4.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Shah M, Foreman DM, Ferguson MW. (1995) Neutralisation of TGF-beta 1 and TGF-beta 2 or exogenous addition of TGF-beta 3 to cutaneous rat wounds reduces scarring. J. Cell. Sci. 108(Pt 3):985–1002.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Cutroneo KR. (2007) TGF-beta-induced fibrosis and SMAD signaling: oligo decoys as natural therapeutics for inhibition of tissue fibrosis and scarring. Wound Repair Regen. 15 Suppl 1: S54–60.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- ten Dijke P, Hill CS. (2004) New insights into TGF-beta-Smad signalling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:265–73.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kopp J, et al. (2005) Abrogation of transforming growth factor-beta signaling by SMAD7 inhibits collagen gel contraction of human dermal fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 280:21570–6.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wang Z, et al. (2007) Inhibition of Smad3 expression decreases collagen synthesis in keloid disease fibroblasts. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg.60:1193–9.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nakao A, et al. (1997) Identification of Smad7, a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 389:631–5.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dooley S, et al. (2003) Smad7 prevents activation of hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis in rats. Gastroenterology. 125:178–91.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chen MA, Davidson TM. (2005) Scar management: prevention and treatment strategies. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 13:242–7.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Terada Y, et al. (2002) Gene transfer of Smad7 using electroporation of adenovirus prevents renal fibrosis in post-obstructed kidney. Kidney Int.61: S94–8.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Niessen FB, Schalkwijk J, Vos H, Timens W. (2004) Hypertrophic scar formation is associated with an increased number of epidermal Langerhans cells. J. Pathol. 202:121–9.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Andriessen MP, Niessen FB, Van de Kerkhof PC, Schalkwijk J. (1998) Hypertrophic scarring is associated with epidermal abnormalities: an immunohistochemical study. J. Pathol. 186:192–200.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lim IJ, et al. (2001) Investigation of the influence of keloid-derived keratinocytes on fibroblast growth and proliferation in vitro. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 107:797–808.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Eming SA, Krieg T, Davidson JM. (2007) Inflammation in wound repair: molecular and cellular mechanisms. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127:514–25.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Moyer KE, Saggers GC, Ehrlich HP. (2004) Mast cells promote fibroblast populated collagen lattice contraction through gap junction intercellular communication. Wound Repair. Regen. 12:269–75.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Noli C, Miolo A. (2001) The mast cell in wound healing. Vet. Dermatol.12:303–13.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ghahary A, Ghaffari A. (2007) Role of keratinocyte-fibroblast cross-talk in development of hyper-trophic scar. Wound Repair Regen. 15 Suppl 1: S46–53.View ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ghahary A, et al. (1996) Collagenase production is lower in post-burn hypertrophic scar fibroblasts than in normal fibroblasts and is reduced by insulin-like growth factor-1. J. Invest. Dermatol. 106:476–81.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Birkedal-Hansen H, et al. (1993) Matrix metalloproteinases: a review. Crit. Rev. Oral. Biol. Med. 4:197–250.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Johnson-Wint B. (1988) Do keratinocytes regulate fibroblast collagenase activities during morphogenesis? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 548:167–73.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fujiwara M, Muragaki Y, Ooshima A. (2005) Keloid-derived fibroblasts show increased secretion of factors involved in collagen turnover and depend on matrix metalloproteinase for migration. Br. J. Dermatol.153:295–300.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Neely AN, et al. (1999) Gelatinase activity in keloids and hypertrophic scars. Wound Repair Regen. 7:166–71.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mauviel A. (1993) Cytokine regulation of metalloproteinase gene expression. J. Cell. Biochem. 53:288–95.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zhang Y, McCluskey K, Fujii K, Wahl LM. (1998) Differential regulation of monocyte matrix metalloproteinase and TIMP-1 production by TNF-alpha, granulocyte-macrophage CSF, and IL-1 beta through prostaglandin-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J. Immunol.161:3071–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- McQuibban GA, et al. (2002) Matrix metalloproteinase processing of monocyte chemoattractant proteins generates CC chemokine receptor antagonists with anti-inflammatory properties in vivo. Blood. 100:1160–7.Google Scholar

- McQuibban GA, et al. (2000) Inflammation dampened by gelatinase A cleavage of monocyte chemoattractant protein-3. Science. 289:1202–6.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Scott PG, et al. (1996) Chemical characterization and quantification of proteoglycans in human post-burn hypertrophic and mature scars. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 90:417–25.View ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sayani K, et al. (2000) Delayed appearance of decorin in healing burn scars. Histopathology. 36:262–72.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zhang Z, et al. (2009) Recombinant human decorin inhibits TGF-beta1-induced contraction of collagen lattice by hypertrophic scar fibroblasts. Burns. 35:527–37.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mukhopadhyay A, et al. (2010) Syndecan-2 and decorin: proteoglycans with a difference—implications in keloid pathogenesis. J. Trauma.68:999–1008.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nedelec B, et al. (2001) Myofibroblasts and apoptosis in human hypertrophic scars: the effect of interferon-alpha2b. Surgery. 130:798–808.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bond JS, et al. (2008) Maturation of the human scar: an observational study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 121:1650–8.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bond JS, et al. (2008) Scar redness in humans: how long does it persist after incisional and excisional wounding? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 121:487–96.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mustoe TA, et al. (2002) International clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 110:560–71.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Durani P, Bayat A. (2008) Levels of evidence for the treatment of keloid disease. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 61:4–17.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mutalik S. (2005) Treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 71:3–8.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Baur PS, et al. (1976) Ultrastructural analysis of pressure-treated human hypertrophic scars. J. Trauma. 16:958–67.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Macintyre L, Baird M. (2006) Pressure garments for use in the treatment of hypertrophic scars—a review of the problems associated with their use. Burns. 32:10–5.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kelly AP. (2004) Medical and surgical therapies for keloids. Dermatol. Ther. 17:212–8.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Reno F, et al. (2003) In vitro mechanical compression induces apoptosis and regulates cytokines release in hypertrophic scars. Wound Repair Regen. 11:331–6.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Van den Kerckhove E, et al. (2005) The assessment of erythema and thickness on burn related scars during pressure garment therapy as a preventive measure for hypertrophic scarring. Burns. 31:696–702.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sawada Y, Sone K. (1992) Hydration and occlusion treatment for hypertrophic scars and keloids. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 45:599–603.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fulton JE, Jr. (1995) Silicone gel sheeting for the prevention and management of evolving hypertrophic and keloid scars. Dermatol. Surg.21:947–51.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Reish RG, Eriksson E. (2008) Scar treatments: preclinical and clinical studies. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 206:719–30.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Phan TT, et al. (2003) Quercetin inhibits fibronectin production by keloid-derived fibroblasts. Implication for the treatment of excessive scars. J. Dermatol. Sci. 33:192–4.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jackson BA, Shelton AJ. (1999) Pilot study evaluating topical onion extract as treatment for postsurgical scars. Dermatol. Surg. 25:267–9.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chung VQ, Kelley L, Marra D, Jiang SB. (2006) Onion extract gel versus petrolatum emollient on new surgical scars: prospective double-blinded study. Dermatol. Surg. 32:193–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Beuth J, et al. (2006) Safety and efficacy of local administration of contractubex to hypertrophic scars in comparison to corticosteroid treatment. Results of a multicenter, comparative epidemiological cohort study in Germany. In Vivo. 20:277–83.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Ho WS, Ying SY, Chan PC, Chan HH. (2006) Use of onion extract, heparin, allantoin gel in prevention of scarring in Chinese patients having laser removal of tattoos: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Dermatol. Surg. 32:891–6.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Asilian A, Darougheh A, Shariati F. (2006) New combination of triamcinolone, 5-fluorouracil, and pulsed-dye laser for treatment of keloid and hypertrophic scars. Dermatol. Surg. 32:907–15.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zurada JM, Kriegel D, Davis IC. (2006) Topical treatments for hypertrophic scars. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 55:1024–31.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Berman B, Kaufman J. (2002) Pilot study of the effect of postoperative imiquimod 5% cream on the recurrence rate of excised keloids. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 47:S209–11.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Berman B, et al. (2009) Treatment of keloid scars post-shave excision with imiquimod 5% cream: A prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J. Drugs Dermatol. 8:455–8.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Prado A, Andrades P, Benitez S, Umana M. (2005) Scar management after breast surgery: preliminary results of a prospective, randomized, and double-blind clinical study with aldara cream 5% (imiquimod). Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 115:966–72.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ferguson MW, et al. (2009) Prophylactic administration of avotermin for improvement of skin scarring: three double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase I/II studies. Lancet. 373:1264–74.View ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bush J, et al. (2010) Therapies with emerging evidence of efficacy: avotermin for the improvement of scarring. Dermatol Res Pract2010:690613.PubMedPubMed CentralView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jalali M, Bayat A. (2007) Current use of steroids in management of abnormal raised skin scars. Surgeon. 5:175–80.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cruz NI, Korchin L. (1994) Inhibition of human keloid fibroblast growth by isotretinoin and triamcinolone acetonide in vitro. Ann. Plast. Surg.33:401–5.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Boyadjiev C, Popchristova E, Mazgalova J. (1995) Histomorphologic changes in keloids treated with Kenacort. J. Trauma. 38:299–302.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Robles DT, Berg D. (2007) Abnormal wound healing: keloids. Clin. Dermatol. 25:26–32.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lawrence WT. (1991) In search of the optimal treatment of keloids: report of a series and a review of the literature. Ann. Plast. Surg. 27:164–78.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Boutli-Kasapidou F, Tsakiri A, Anagnostou E, Mourellou O. (2005) Hypertrophic and keloidal scars: an approach to polytherapy. Int. J. Dermatol. 44:324–7.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jaros E, Priborsky J, Klein L. (1999) Treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars with cryotherapy [in Czech]. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). Suppl. 42:61–3.Google Scholar

- Yosipovitch G, et al. (2001) A comparison of the combined effect of cryotherapy and corticosteroid injections versus corticosteroids and cryotherapy alone on keloids: a controlled study. J. Dermatolog. Treat.12:87–90.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sharpe D. (1997) Of apples and oranges, file drawers and garbage: why validity issues in meta-analysis will not go away. Clin. Psychol. Rev.17:881–901.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rusciani L, Rossi G, Bono R. (1993) Use of cryotherapy in the treatment of keloids. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 19:529–34.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zouboulis CC, Blume U, Buttner P, Orfanos CE. (1993) Outcomes of cryosurgery in keloids and hypertrophic scars: a prospective consecutive trial of case series. Arch. Dermatol. 129:1146–51.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Har-Shai Y, Amar M, Sabo E. (2003) Intralesional cryotherapy for enhancing the involution of hypertrophic scars and keloids. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 111:1841–52.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Poochareon VN, Berman B. (2003) New therapies for the management of keloids. J. Craniofac. Surg. 14:654–7.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zuber TJ, DeWitt DE. (1994) Earlobe keloids. Am. Fam. Physician. 49:1835–41.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guix B, et al. (2001) Treatment of keloids by high-dose-rate brachytherapy: a seven-year study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 50:167–72.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ogawa R, Mitsuhashi K, Hyakusoku H, Miyashita T. (2003) Postoperative electron-beam irradiation therapy for keloids and hyper-trophic scars: retrospective study of 147 cases followed for more than 18 months. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 111:547–55.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Apfelberg DB, et al. (1984) Preliminary results of argon and carbon dioxide laser treatment of keloid scars. Lasers Surg. Med. 4:283–90.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Alster TS, Handrick C. (2000) Laser treatment of hypertrophic scars, keloids, and striae. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 19:287–92.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tanzi EL, Alster TS. (2004) Laser treatment of scars. Skin Therapy Lett.9:4–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Alster T. (2003) Laser scar revision: comparison study of 585-nm pulsed dye laser with and without intralesional corticosteroids. Dermatol. Surg.29:25–9.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Alster TS, Williams CM. (1995) Treatment of keloid sternotomy scars with 585 nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser. Lancet. 345:1198–200.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dierickx C, Goldman MP, Fitzpatrick RE. (1995) Laser treatment of erythematous/hypertrophic and pigmented scars in 26 patients. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 95:84–92.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chan HH, et al. (2004) The use of pulsed dye laser for the prevention and treatment of hyper-trophic scars in Chinese persons. Dermatol. Surg.30:987–94.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fiskerstrand EJ, Svaasand LO, Volden G. (1998) Pigmentary changes after pulsed dye laser treatment in 125 northern European patients with port wine stains. Br. J. Dermatol. 138:477–9.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hermanns JF, Petit L, Hermanns-Le T, Pierard GE. (2001) Analytic quantification of phototype-related regional skin complexion. Skin. Res. Technol. 7:168–71.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jimenez SA, Freundlich B, Rosenbloom J. (1984) Selective inhibition of human diploid fibroblast collagen synthesis by interferons. J. Clin. Invest.74:1112–6.PubMedPubMed CentralView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Berman B, Duncan MR. (1989) Short-term keloid treatment in vivo with human interferon alfa-2b results in a selective and persistent normalization of keloidal fibroblast collagen, glycosaminoglycan, and collagenase production in vitro. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 21:694–702.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tredget EE, et al. (1998) Transforming growth factor-beta in thermally injured patients with hyper-trophic scars: effects of interferon alpha-2b. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 102:1317–28; discussion 1329–30.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tredget EE, et al. (1998) Transforming growth factor-beta in thermally injured patients with hypertrophic scars: effects of interferon alpha-2b. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 102:1317–30.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Espana A, Solano T, Quintanilla E. (2001) Bleomycin in the treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars by multiple needle punctures. Dermatol. Surg. 27:23–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bodokh I, Brun P. (1996) Treatment of keloid with intralesional bleomycin [in French]. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 123:791–4.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Naeini FF, Najafian J, Ahmadpour K. (2006) Bleomycin tattooing as a promising therapeutic modality in large keloids and hypertrophic scars. Dermatol. Surg. 32:1023–30.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Saray Y, Gulec AT. (2005) Treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars with dermojet injections of bleomycin: a preliminary study. Int. J. Dermatol. 44:777–84.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Apikian M, Goodman G. (2004) Intralesional 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of keloid scars. Australas. J. Dermatol. 45:140–3.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fitzpatrick RE. (1999) Treatment of inflamed hypertrophic scars using intralesional 5-FU. Dermatol. Surg. 25:224–32.PubMedView ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nanda S, Reddy BS. (2004) Intralesional 5-fluorouracil as a treatment modality of keloids. Dermatol. Surg. 30:54–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar